(Courtesy: Mark Schuver)

Whispers of the Wheel: A Journey Through Time at Turner’s Mill.

You first hear about Turner’s Mill in a corner booth of a sleepy- themed coffee shop—just a quiet exchange between locals, their voices low and familiar. “Still out there,” one says, “just the wheel left now.” Intrigued, you follow their directions, winding through the thick green heart of the hills, past limestone bluffs and creeks that glint like glass. The road narrows, the trees press closer, and then the valley opens like a held breath. And there it is! Towering and unmoving, this gigantic steel wheel rises from the earth, rusted but regal. All that remains of a once-mighty mill, its walls and water channels are long vanished. This magnificent wheel stands alone, heavy with silence, the last witness to the hum and hammer of a time that’s gone—but not quite forgotten.

Turner’s Mill is a place of stillness, where nature has gently reclaimed the land that once echoed with grinding gears and rushing water. The stone foundation is softened by moss, and wildflowers sway where mill workers once stood. The air is filled with birdsong, the rustle of leaves, and the distant murmur of the Eleven Point River weaving through the trees. The massive wheel still draws hikers, history buffs, and curious wanderers who pause beneath it in quiet awe. There are no crowds here—just the whisper of the past, carried on the breeze, and the sense that you've stumbled upon something sacred, weathered, and enduring.

Turner’s Mill might seem like just a roadside curiosity — a weathered, towering steel wheel standing sentinel over a quiet creek — but this spot was once the heart of a thriving rural community. A place where pioneer spirit met innovation, where the sound of turning water and sawing timber filled the air, and where neighbors gathered not just to work, but to live and share stories.

If you listen carefully, you might still hear those echoes — the laughter of children playing in the creek, the rhythmic creak of belts and pulleys, and the whisper of the Ozarks winds carrying memories through the trees.

(Courtesy: Wikipedia)

On a good day, 1.6 million gallons of water pour from this timeless bluff in Turner, Missouri— a steady, quiet force that remains committed, no matter how much the world around it changes.

The Spring That Started It All.

At the core of Turner’s Mill is Turner Spring, a powerful natural fountain bursting from the earth with over 1.6 million gallons of crystal-clear water every single day. It flows steadily from a sheer bluff, carving a cool stream through mossy rock beds and towering sycamores.

Before Turner's Mill gained popularity, its spring was a quiet haven for Native Americans, frontiersmen, Civil War soldiers, pioneers, and wanderers alike. Long before settlers arrived, Native American tribes stayed close to the spring, relying on its waters and the surrounding land for hunting and sustenance. Later, others came seeking the same comforts—a place to rest, refill, and find a moment of peace. The steady, cool flow of the spring offered not just refreshment, but a deep, lasting sense of connection to the land.

(Courtesy: Richard Crabtree)

John Lechter "Clay" Turner, the visionary pioneer who transformed Turner’s Mill, stands as a symbol of innovation and resilience in early American industry. His craftsmanship and entrepreneurial spirit helped shape the local community and economy.

Enter John Turner: Builder, Dreamer, Doer!

According to Richard Crabtree, Ozarks History And Photographs, the land was acquired in 1860 by G.W. Decker, who recognized the spring’s potential to power a gristmill.

Decker built a set of stone burrs and a modest wooden overshot wheel that would set to turn as water rushed over it from above. The mill quickly became a lifeline for pioneer families scattered across the rugged Ozark hills — a place to transform grain into nourishment and to connect with others braving the wilderness. However, a tremendous change was coming that would shape this rural landscape tremendously. Not being up for the challenge, Decker soon sold the mill to T. M. Simpson of Oregon County Missouri.

Fast forward to 1888, when a determined John L. “Clay” Turner — a man with an eye for opportunity and a heart for community — bought the mill and the surrounding 160 acres of forest and farmland. However, John wasn’t a Missouri native, which made him all the more courageous. Born in 1861, he came from Virginia, drawn westward by the promise of land, industry, and a new beginning in the wild Ozarks. Mr. Turner would acquire the mill from T.M. Simpson, along with blacksmith tools, 200 pounds of nails, 75 hogs and lumber. In 1888, there was something else that he needed and that came in the beauty of a woman named Elizabeth D. "Bettie" Simpson. They soon married. How did they meet in such a desolate area? Elizabeth was a relative of T. M. Simpson.

Together, they would raise a family of six children, one passed as an infant, and live the life they always dreamed of. As the children grew, they would enjoy the simple times of growing-up in the Ozarks, and yes, they would also learn a hard work ethic from working in their father's mill.

Lottie Ollie Turner Sisco 1893–1979

Letcher E. Turner 1895–1984

Infant Son Turner 1897–1897

Kyle Everett Turner 1900–1973

William Harvey Turner 1903–1987

Oba A Turner 1906–1988

Woodrow W Turner 1913–1997

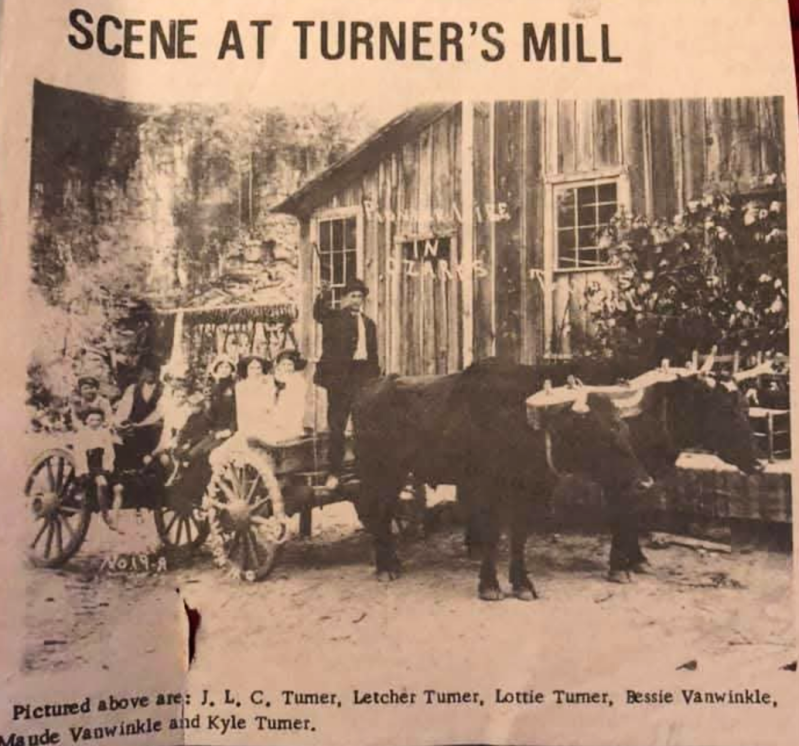

(Courtesy: Martha Burton Long)

A familiar sight, John L. "Clay" Turner and family could be seen venturing out among the small town of Surprise, Missouri, pulled by their two friendly oxen, Nig and Red.

(Courtesy: Steemit)

A rare and seldom-seen glimpse behind the scenes at Turner Mill, showcasing the hardworking crew in the mill area — a snapshot of industrial life that few today ever get to witness.

(Courtesy: Jenny Underwood)

The Giant Wheel of Turner's Mill: A colossal marvel made of several tons of iron, built to harness the mighty 1.6 million gallons of Ozark spring water flowing daily from Mother Earth.

The Goal Was To Harvest With The Water!

J.C. Turner was guided by a rare obsession: finding the perfect spring. Not just any water source would do. Turner sought a hillside spring powerful enough to operate an overshot water wheel — a design that demanded more elevation, more force, and more ingenuity than the standard undershot wheels common in the region. His aim was clear: to build a mill that could grind and saw with unmatched hydro power. Amid the dense forests and rugged bluffs near the Eleven Point River, Turner found what he was looking for — a spring flowing from a cave in limestone rock. In the early 1900's, with the willpower and the commitment of family and a few select neighbors, J.C. Turner would completely make over what now was being locally known as Turner's Mill. He rebuilt the wheel and enlarged the wood flume that fed the mill and he also added a turbine and boiler. Needing to make more room for production and clearance underneath, J.C. and his crew dynamited the immediate river area. Blasting could be heard on the Eleven Point River as John Turner was making way for commerce. With the several tons wonder of a new overflow wheel, Turner's Mill was able to power a large sawmill, thus realizing a plan that had been successfully set into motion, literally!

Among the towering oaks and straight-backed pines, John Turner had successfully constructed a mill that turned nature’s force into enterprise. Turner’s decisions reflect not only technical knowledge but a relentless pursuit of efficiency — a man who saw potential where others saw isolation. Turner was no ordinary miller. He envisioned a place that was more than a simple mill- a full-fledged industrial hub where grain could be ground, lumber sawed, and tools crafted. Under his hands, the mill was rebuilt into a towering four-story structure, equipped with a complex network of belts, pulleys, gears, and turbines.

John’s mill housed a sawmill, planer, drill press, lathe, and other machines powered entirely by the spring’s flow. Logs floated down the nearby Eleven Point River were cut into lumber. Wheat and corn were ground into flour and meal. The mill became a vital economic and social anchor for not only the locals but also supplying vital goods for markets nationwide!

According to a family relation, Lewis A. Simpson of Alton, Mo., when J.C. Turner added the ability to saw wood, he gained more customers. Besides his largest customer, Springfield Wagon Works in Springfield Missouri, he also supplied lumber to the Frisco Railroad. Most of this wood and lumber would be hauled up to Winona, Missouri to be loaded on the Frisco Current River Branch and transferred to Springfield.

Good word spread like wildfire through the Eleven Point River region and the demand for skilled workers was overflowing with potential. Uniquely, workers came from near and far. Going to work at the mill was a several days to a week adventure. Eager workers had to camp by the mill and wait for their turn to earn a wage. Most times, entire families would come up to Surprise and would camp, fish, play in the water while their father's would wait in line for their turn at the mill.

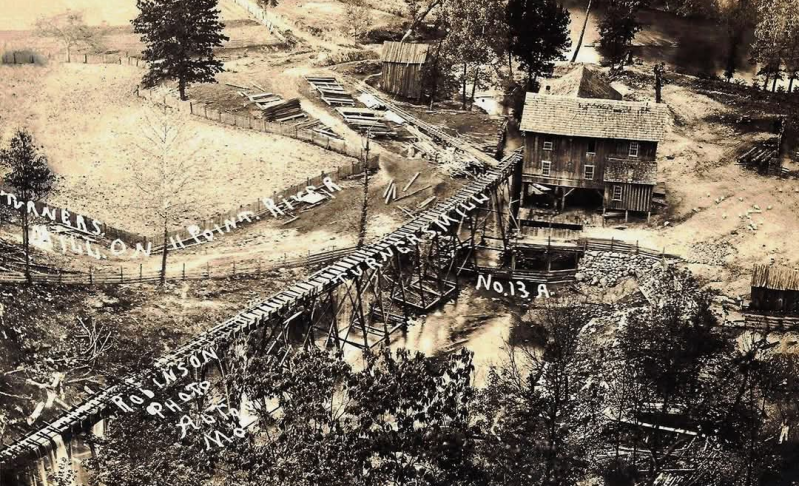

(Courtesy: Richard Crabtree)

Turner’s Mill stands as a testament to the incredible time and labor invested in its construction — a place where not only grain was ground but wood was meticulously manufactured on-site, showcasing the skill and dedication of its builders. Circa 1942.

(Courtesy: Richard Crabtree)

An overshot of Turner's Mill, photographed from the very prominent bluff above, shows just how developed Turner's Mill really was!

St. Louis Post Dispatch, 1932.

Could it be a very impressed reporter? Most accounts say the wheel is in the 20 plus range of feet, this reporter said it was 36 feet. Whatever the number, it is gigantic!

Town Called Surprise Came Later

One of John Turner’s more whimsical legacies was the creation of a post office right inside the mill. When asked what to name it, he reportedly wrote “Surprise” — half in jest, because he never expected the government to approve such an unusual name. To everyone’s delight, they did!

Thus, the tiny village of Surprise, Missouri was born!

Hard work was one way to move toward opportunity but there was another, education. In 1897, the Turners donated land and 2000 links (lumber) to build what would be known as Surprise School. Of course, worker's children would go there and learn reading, writing and arithmetic. The school was located south of the mill area.

J.C. was all about community. He was postmaster for a bit, hired the first school teacher, had a general store and oversaw construction of a clever bridge designed to withstand floodwaters by allowing water to flow right over it, rather than washing it away.

At its peak, Surprise was home to roughly 50 residents — a close-knit community bound by the rhythms of the mill, the seasons, and the forest.

Life was good. Campfires lit the evenings, and children played in the cool creek as families waited days for their flour or lumber orders. The mill wasn’t just a workplace, it was an extended family. It was the "heart and soul" of a thriving Eleven Point River area.

Candid Recollections of Turners’ Mill and Surprise, Mo.

According to the Oregon County History Group member, Jenny Underwood, the post office and school were at Turner Mill by 1885. John "Clay" Turner was appointed postmaster and held the position until the office closed in 1925. Art Green assisted in the post office and store. He had a college degree, kept good records, was good in mechanics and helped keep the mill machinery in top shape. Surprise School was ½ mile down river from Turners near Stinkin’ Pond Hollow.

Workers at Turners’ Mill included “Slim Indian” Redburn, “Mock,” Ab Hill and his grandchildren, the Van Winkles.

Some people, called the “Spanish Lady and her man” came to Turners’ Mill in a covered wagon. They camped and searched a certain hollow. They dug either for gold or buried treasure.

Turners Mill was self-sustaining. Crops of grain were grown, milled, and baked into bread. Sorghum cane was raised and each autumn boiled into molasses. The tobacco crop was harvested and hung in drying sheds, and later twisted for chewing or smoking in their corn cob pipes. John "Clay" Turner drove his oxen, Nig and Red, to skid logs to the mill and to plow his farmland along the Eleven Point River from Little Hurricane to Stinkin Pond Hollow.

When people asked Turner why he named the post office Surprise, he answered, “I was really surprised when I first saw this place.”

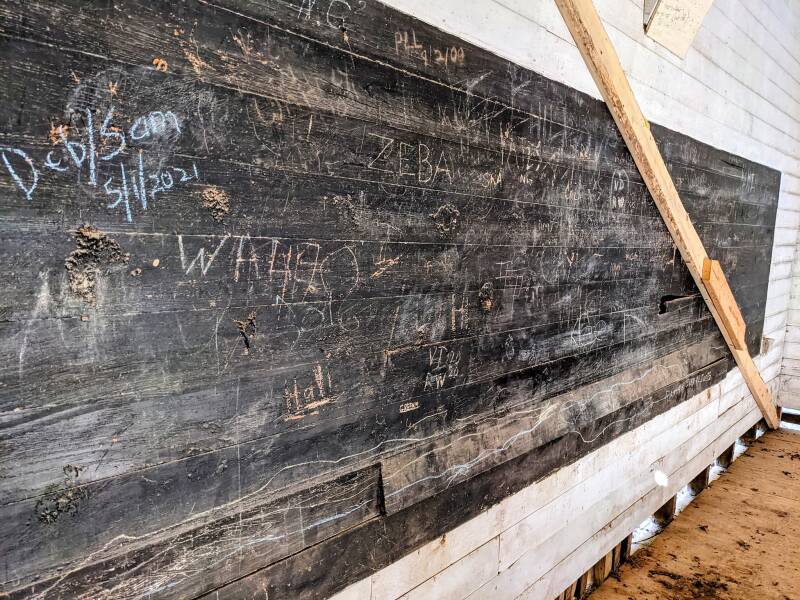

(Courtesy: Joan Cozort)

Historic Turners’ Mill was acquired by the Forestry Service. Surprise School is on the National Historic Register; therefore, it was saved for posterity. Of the rest, only the rustic over-shot wheel in the spring branch escaped the demolishment. Circa, 2021.

(Courtesy: Joan Cozort)

You can almost hear the clattering of footsteps and children's chatter within the remains of the Surprise, Missouri school, whose land was donated and developed by none other than John Turner. By the mid-1940s, the school closed, as younger generations left for the lure of towns and cities, and the tight-knit village community slowly unraveled. Circa, 2021.

A Closer Look At The Giant: A Steel Wheel with a Story!

(Courtesy: Jenny Underwood)

This giant steel overflow wheel wasn’t just machinery—it was J.C. Turner’s hard-fought vision made real. In a remote rural corner, he recognized the need, faced the challenge, and endured the long, difficult journey to bring it here—each turn a testament to his relentless drive to craft something beautiful against all odds.

According to Ms. Jenny Underwood, Oregon County History Group, John L. "Clay" Turner took his mill into the modern age with an awe-inspiring upgrade — a massive 26-foot steel overshot water wheel! This gigantic all-American steel overshot wheel was ordered from Indiana in 1914. Shipped by train to Fremont, the Turners hauled it to the mill site in a wagon. They assembled the wheel with the help of Art Green, Will Steward, and John Brown, head carpenter, and all crew pushed to build a new water race. It was a calculated move that kept his operation running day and night. J.C. Turner quickly became a legend within the Eleven Point Rivers' rolling hills. Not only did he supply jobs, but he also had the vision to make this rustic area something that could be "put on the map" far and wide!

(Courtesy: Richard Crabtree)

Proclaiming business to be made! In the teens of a new century, J.C. Turner proudly announces his modernized mill—now driven by a towering steel overflow wheel—marking a bold step forward for progress in Surprise, Missouri. Publisher was the South Missourian Democrat, 1915.

(Courtesy: Richard Crabtree)

If you're going to do something, do it right! Major upgrades allowed production to occur day and night. Circa, 1915.

The Slow Fade of Surprise Amid a Changing World.

(Courtesy: Matt Chaney)

Before Time and demolition took it away... if you listen closely, you can still hear the hum of Turner's Mill — echoes of laughter, long days, and sweat-soaked shirts. A place built on dedication, where stories of turn-of-the-century work will forever linger. Circa, 1936.

Like many small rural communities, Surprise's fortunes begin to wane as the 20th century unfolded a time when the world around it was changing rapidly and profoundly. The post office closed in 1925, signaling the beginning of the village’s quiet decline. This period coincided with major events that reshaped America and the globe. The Roaring Twenties brought rapid industrialization and urban growth, drawing many rural residents toward cities in search of new opportunities. Just a few years later, the Great Depression of the 1930s cast a long shadow over the country, bringing economic hardship and uncertainty to communities everywhere. For small towns like Surprise, which relied heavily on local mills, farming, and timber, the economic downturn meant fewer customers, less investment, and dwindling population as families moved on or struggled to survive.

Meanwhile, technological advances like the widespread adoption of electricity, automobiles, and improved roads gradually reduced the need for local mills. Grain and lumber could be processed in larger, more efficient factories elsewhere, and rural postal routes consolidated.

By the mid-1940s, the school closed, as younger generations left for towns and cities, and the tight-knit village community slowly unraveled.

After closing the mill in 1930 and John "Clay" Turner’s death in 1933, the beating heart of the town, fell silent. The steady murmur of machinery and life gave way to the quiet reclaiming of the land by the forest. People reluctantly moved to find a newfound sense of happiness.

It's bittersweet how time shifts from one purpose to another. In the post-production era, Turner's Mill was still booming but now in a different way. It was a place to picnic, camp, boat and fish. Sadly, as the years went by, the now abandoned mill lost purpose and took a beating from floods and weather in general.

Feeling the need to preserve a local cherished piece of heritage, The U.S. Forest Service - Mark Twain National Forest acquired the 917 acre tract in 1963. Sadly demolition of the mill was the safest thing to do, however, the Surprise School was added to the National Historical Registry and spared.

John L. "Clay" Turner’s final resting place is just a few miles south, in the Bailey Cemetery in Alton, Missouri, where he, Bettie, and most of their children lie beneath quiet oaks and wide Missouri skies. Their graves mark the end of an era — but also a beginning, as their story continues to echo through the forests and streams of the Ozarks.

Staying close to Turner's Mill, the final resting place for "Clay" and "Bettie" Turner, as well as most of their offspring can be found at the Bailey Cemetery, in Alton, Missouri. Perhaps proving a strong testament that they were very common and approachable people within a beloved community, their nicknames were used on the headstone.

(Courtesy: Steemit)

Once the heartbeat of a bustling Turner's Mill, now the old wheel rests in silence with no purpose except for occasional visitors— embraced by time and youthful trees.

A Beacon in the Wilderness

Today, all that remains of that vibrant community and industrious mill is the gentle trickle of Turner Spring and the coveted towering steel wheel — standing stoic and alone amidst the woods.

Rising above moss-covered stones and framed by towering trees, the wheel serves as a beacon reaching into the wilderness — a silent sentinel marking where lives were built, work was done, and a town once thrived.

Its rusted spokes and massive iron frame invite visitors to pause and reflect. It's more than a piece of machinery — it is a monument to resilience, ingenuity, and the passage of time. Most of all, it's a visual testimony from the commitment and ingenuity of a "larger than life" dreamer, J.C. Turner.

Why Turner’s Mill Still Matters

Turner’s Mill is far more than a forgotten relic. It is a story carved in iron and stone, told through water and wood. It is a reminder of a time when people worked hand-in-hand with the land — using natural power to build communities, craft livelihoods, and forge connections.

For locals and visitors alike, Turner’s Mill offers a chance to step back, to listen, and to feel a quiet but powerful link to the pioneers who came before us.

And standing beside that great steel wheel — watching the spring water trickle past and imagining the mighty turns it once made — it’s easy to feel the pulse of history still turning quietly in the Ozarks.

How to Visit:

Thanks to the U.S. Forest Service, Turner’s Mill remains a preserved historic site along the Eleven Point National Scenic River. Located at the Turner Mill North Access (river mile 22.3), it is open year-round for day-use from respectful visitors.

Here, hikers and history lovers find picnic tables, vault toilets, and trails that lead to the steel wheel, the mill’s concrete flume, and the shimmering spring itself. It’s a place to slow down, breathe deeply, and connect with a past that still hums softly beneath the forest canopy.

📍 Location: Turner Mill North Access, Eleven Point River, Oregon County, MO

🚗 Directions: From Alton, MO, take Hwy 19 north → Forest Road 3152 → FR 3190

🕓 Open: Year-round, sunrise to sunset (day-use only)

🛶 Camping: Available just across the river at Turner Mill South with boat launch, fire rings, and rustic charm

Enjoyed this? Here are more stories you might like!

(Courtesy: Historical Archives)