The Kindness That Cost Everything: The Murder of Dr. J.C.B. Davis.

In early 1937, Willow Springs, Missouri, was the kind of place where front porches stayed swept, doors were rarely locked, and kindness wasn't just practiced—it was treasured. Tucked into the folds of Howell County, the town moved at the steady rhythm of train whistles, grazing cattle and crop seasons. There was a strong trust system that ran through the area. Neighbors helped neighbors and sometimes, if money was tight, locals happily paid for services with eggs or tools. It was greatly accepted, even for something as serious as medical services. If you were ailing, you didn't need much—just your word and someone like Dr. J.C.B. Davis.

But a small town's core of trust was attacked on a cold January afternoon, when the man who had delivered so many babies and eased so many aches and pains walked out of his office and tragically disappeared.

(Courtesy: The Willow Springs News)

A very young and handsome James Davis. A man of many gifts and always putting others first, he nurtured minds through being a professor and then later, as a doctor who healed sick patients.

Who Was Dr. James Clinton Bradford Davis?

J. C. B. Davis was born on November 5, 1870, in Howell County, Missouri. James was one of many siblings and grew-up cherishing the small town ways of helping your neighbor when they needed it most. As he grew older, James decided to help others in a way that they could use all of their lives. He decided that he wanted to become a teacher. James Davis was a Cumberland Presbyterian and Democrat and he excitedly began his teaching career after graduating from Mountain Grove Academy in 1891. He married Mildred Payne, local resident of Willow Springs and soon, they moved to Winona and a young James Davis began his teaching career at Winona High School. They had one child together but a year after the birth of their daughter Cleora, tragedy struck. Wife Mildred unexpectedly passed, she was a young age of 24.

With nine years of experience in rural and graded schools, he served as principal and instructor at several institutions, including Willow Springs High School and Winona High School, which he helped organize. Though he was recognized as a professor and nurtured young minds with passion and purpose, James Davis aspired to do even more—his deeper calling was to cure illnesses and help ease others pain through medicine and healing. Upon receiving the necessary training and certification, J.C.B. knew his newfound purpose would be to serve his hometown community of Willow Springs. He eventually found love again and married a lady by the name of Ms. Clara Dunne. James became a father for the second time, this time to a baby boy named Harold Davis.

Finally realizing true happiness again, Davis became wholeheartedly known as the town’s trusted physician. No matter the time of the day or night, irregardless of the weather or even if he was not feeling well, Dr. Davis made house calls—by lantern when needed. Understanding the lay of the land and that sometimes days were long and money was short, Dr. Davis even accepted produce or other township services in lieu of payment. His modest office near Main Street saw countless acts of compassion: broken limbs set, fevers cooled, newborns welcomed.

But there was more to Dr. Davis than what met the eye. For those who were patients, it was clear upon a gentle handshake and wide smile that they were going to be treated with compassion. In fact, Dr. Davis didn’t just tend to ailments; he listened to fears, offered hope in hushed homes, and embodied the belief that a doctor’s true reward was helping people—no matter the cost.

Sadly, Dr. Davis' kindness would demand a price too dear. In the blink of an eye, a town's foundation of trust and innocence would be shaken to the core.

The Cold Winds of Change Blew as a Stranger Came to Town

On the afternoon of January 26, 1937, and according to G.F. Thomas, a Willow Springs local who witnessed the encounter, a young stranger—a tall, dark-complexioned man in a fur-collared overcoat—approached Dr. Davis with urgency. The man claimed there was a medical emergency involving a "Mr. James" approximately six miles into the countryside, in the direction of West Plains. Without hesitation, the doctor, known for his compassion and commitment, agreed to assist. He stopped briefly at his office, gathered his medical bag and informed his assistant, Geraldine Fromwell, of the change in plans and told her he’d be back soon. He then entered the stranger’s vehicle and both drove off—leaving his own car behind.

Several hours passed and now fearing something was out of the ordinary in the wee early hours of January 27, 1939, Mrs. Davis reported her husband missing. Initially, she was not overly concerned, accustomed to her husband’s long, unpredictable obstetric calls. But as hours passed and his car remained unmoved, the gravity of the situation became undeniable.

State police, led by Captain L.B. Howard of Springfield, launched an investigation and quickly uncovered a troubling detail: no individual named "Mr. James" was known to reside anywhere between Willow Springs and West Plains. This revelation deepened the mystery and raised disturbing questions. Why would a stranger invent a name? Where had they gone? And why target a man as humble and civic-minded as Dr. Davis— who, by all accounts, was not wealthy and certainly could not offer a ransom? Slowly but surely, the Davis family and local residents were left to grapple with the growing fear that one of their beloved may have been deliberately abducted under the guise of a desperate call for help and sinister motive.

(Courtesy: The Willow Springs News)

And the search was on for a beloved neighbor and trusted care provider, Dr. J.C.B. Davis, who vanished under suspicious circumstances in January 26, 1937, after reportedly being lured into a car by a man acting on behalf of a patient. The next day, Clara Davis reported her husband missing to authorities and the Missouri State Highway Patrol began an investigation.

The Note and a "White Flag"

As every excruciating hour past, Clara Davis and a community of worried town folk braced for something that nobody would ever think could happen within the safe confines of Willow Springs, Missouri. Where was Dr Davis and how would they find him? The answers would come soon enough from a weathered and handwritten letter.

Evidence indicated that this plain white sheet of paper with distinct handwriting was mailed from West Plains and postmarked January 28, 1937, and was received the following day by Clara Davis, Friday the 29th. FBI agents were sent to Willow Springs to join the investigation. Opening with the salutation "Dear friend," handwriting, meaning the kidnapper had forced Davis to write his own ransom letter, "don’t call the police. Instructions will follow. I am in danger!" It demanded that $5,000 be paid in four $1,000 bills, nine $100 bills, and five $20 bills. It threatened the doctor with death if the family did not comply, and it contained instructions for delivering the money.

The instructions for delivering the money was as unique as the situation. A white "flag of cloth" was to be placed along the highway leading towards Ava, Mo., and would mark the spot to leave the money. Davis' son-in-law, following the letter's instructions, drove along the road between Willow Springs and Ava after dark looking for the potentially life-saving "white flag" that the letter said would mark the spot where the ransom money was to be dropped, but the son-in-law, his vision obscured by heavy fog, failed to find a "white flag". Meanwhile, volunteers combed woods and creeks under the watchful eyes of the Missouri Highway Patrol, FBI and other agencies. No exchange occurred and nothing new was found, and then it happened.

The Black Bag

(Courtesy: West Plains Daily Quill)

Pictured is farmer, Alvin Brixey, who unexpectedly discovered Dr Davis' medical bag and initially was a suspect. The black bag was found snagged in some debris at the edge of the Norfolk River, southwest of Willow Springs and near Grimmet, Mo., (on the way to Ava, Mo.), which is where Robert Kenyon lived with his family.

The same day Clara Davis received the ransom note, January 29, 1937, Davis' medical bag was found about thirteen miles southwest of Willow Springs in the North Fork River. Alvin “Buster” Brixey was taking his cows to water at the North Fork River near Hammond Camp, when he spotted a black bag lodged in some driftwood. He took off his shoes and waded in the icy river to retrieve the bag. The contents proved to be the medical bag of Dr. J.C.B. Davis. Buster took the bag to the nearby CCC (Civilian Conservation Corp) Camp at Hammond and turned it over to Capt. John Runyon. Apparently, there was an address found in the bag indicating that Dr. Davis was the camp doctor. Buster had no idea that Dr. James Davis of Willow Springs had been kidnapped and would later be found murdered. Buster was questioned about the crime since he had the doctor’s bag and was an acquaintance of the later to be accused, Robert Kenyon, but was exonerated. With Dr. Davis' medical bag being held as evidence, fears had been raised that the doctor had already been foully dealt with, but nevertheless, the search continued, only this time to possibly recover the body of a beloved community neighbor and caregiver.

Clues Shedding Light On Darkness

On Monday, February 2, Clara Davis received a second note, written this time in unfamiliar handwriting, renewing the demand for $5,000 in ransom and directing that it must be delivered by 9:00 p.m. February 4th.

Meanwhile, acting on a tip from a person who had seen Dr. Davis and a young man in an automobile on the day of the doctor's disappearance, the Missouri Highway Patrol Officers accelerated the pace even more and eventually located an automobile matching the witness's description at the home of Daniel Kenyon in Grimmet, Missouri. Grimmet was a small community northwest of West Plains (closest town was Ava, Mo.), about halfway between West Plains and the North Fork River, where the medical bag was found.

Officers identified landowner Daniel Kenyon's twenty-one-year-old son, Robert, as a suspect in the kidnaping, and during a search of the residence, they found a notebook pad with the top sheet containing barely legible indentations that matched the words and handwriting of the second ransom note. Young Kenyon was also in possession of a .25 caliber automatic pistol, and it was determined that the suspect's automobile, used in the kidnapping of Dr. Davis, was found on the premises. Consummating a behavior of Robert Kenyon being a repeat offender, the vehicle in possession matched the credentials of a stolen car from Rolla that had been taken a few months earlier.

Kenyon perhaps knew that he couldn't "swim the surmounting tidal wave" of evidence and not long into the investigation, confessed and led officers to Davis’ body near rural Olden, Mo. Coldly, he explained that he shot Davis while the doctor was trying to write a check under duress. Kenyon said that things got heated after he tried to get Davis to write several ransom notes. His motive was he needed money for clothing and to marry his girlfriend.

(Courtesy: The Willow Springs News)

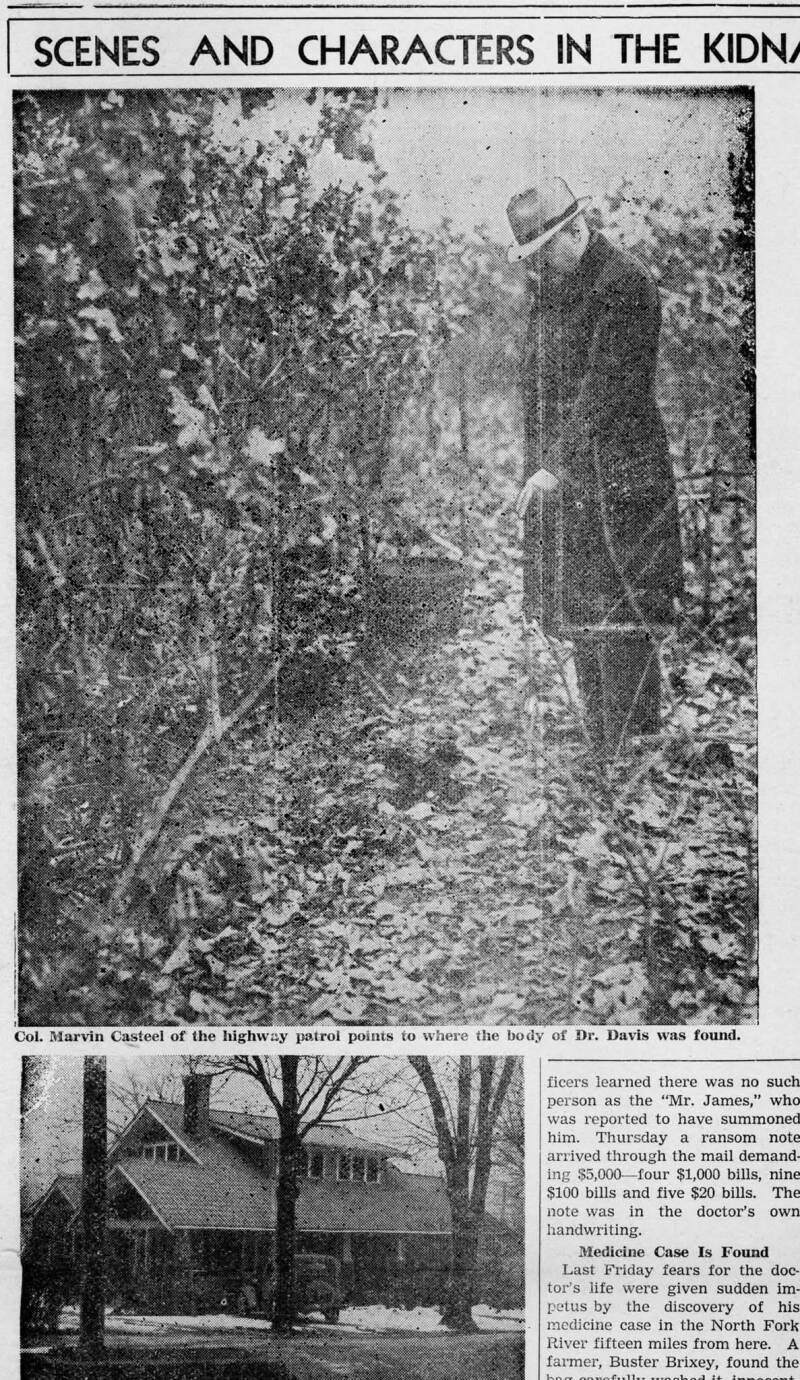

Pictured 1st above: Actual investigation photo of exactly where Dr. Davis was murdered and abandoned by Robert Kenyon. The body area was about 100 yards from the rural highway near Olden, Mo. It was here that Dr. Davis was found face down, several bullets inflicted and in one hand, gripping his gloves and in the other, his checkbook.

Picture 2nd above: The house where Dr Davis and his family lived. Still standing today, you can't help but wonder if its walls still deal with the painful memories of Dr. Davis death.

(Courtesy: West Plains Quill)

You're looking at evidence. Ms. Opal Welch, was the 18-year-old sweetheart of Robert Kenyon. She was the sole motive, according to Robert Kenyon, for the murder of Dr. J.C.B. Davis. Opal had said that they had to postpone the wedding until she got some "new clothes."

On February 6, 1937, Robert Kenyon gave an oral confession to Colonel Casteel and FBI agents.

On February 8, 1937, he signed a detailed written confession, admitting planning the kidnapping for about two weeks and the shooting.

Physical evidence supported the confession: ballistics experts linked bullets found in Davis’ glove to Kenyon’s pistol, and forensic examination connected the ransom notes to Kenyon’s handwriting and the notebook he possessed.

After being taken into custody, things got hectic for Kenyon. Robert was first taken to the Willow Springs jail but was eventually whisked away to Kansas City early the same morning (Feb. 3) to avert feared vigilantism. Kidnapping and first-degree murder charges were filed against him later the same day. His trial was set and held in July of 1937, at the Oregon County seat of Alton, Mo., on a change of venue, due to publicity concerns.

(Courtesy: Mo. Dept. Of Corrections)

Not really known for being an intelligent criminal, Robert Kenyon had many flaws in his crime and it was just a matter of time before he would be caught, tried and executed.

(Courtesy: West Plains Quill)

Pictured left: Robert Kenyon shortly after arriving in a Kansas City jail facility. He was relocated due to concerns of local vigilante repercussions.

Pictured right: Robert Kenyon's father Daniel, who was quoted, "I reckon he was in it all right but I don't believe he did the shootin'."

In a Killer's Own Words

In the days leading up to locating a suspect, confession and recovery of doctor Davis' body, there had been no voice of Robert Kenyon... until now.

The confession of Robert Kenyon shocked even the most hardened members of law enforcement. In a chilling and matter-of-fact tone, he began to recount the events that had long haunted the shadows of a small town in 1937.

What follows is a rare and disturbing glimpse into the mind of a killer—his confession, as preserved in the records of the State of Missouri vs. Kenyon and before the Missouri Supreme Court. It details the calculated kidnapping and brutal murder of Dr. Davis with unnerving precision. In a bizarre twist, Kenyon names a subject, "Nighthawk" as initially part of the crime and then later, recants this part of the testimony.

"I mailed this note myself, dropping it in a mail box on the public square while the doctor was with me and did not go to the Post Office. The doctor did not do much talking while he was in my car. After mailing this first ransom note we left town, driving on the Dora Road about fifteen or eighteen miles, as near as I can recall. We stopped on a bridge on the Dora Road, which is located near North Fork Creek, and I told the doctor to throw his medicine kit in the creek, which he did. We then drove on the Dora Road to Highway No. 14 and after more driving around we went back to Highway No. 63. We went on Highway No. 63 to the North side of Olden, Missouri.

"We stopped on the highway near a pond and I told the doctor to get out of the car and we went in the brush where I was to have him write more ransom notes. He took his check book out of his pocket and wanted me to write a check for $5,000.00 to turn him loose, which I refused to accept. He kept talking to me trying to get me to accept the check, but I would not do it. I had a piece of paper and a pencil and I wanted him to put his check book away and write more ransome notes. I was sitting on the ground and he was standing up. He made a jump for me and I had to shoot him. I emptied my gun into him. I believe the clip in the pistol was full, and, if so, there would be six shells in it. This happened, as near as I can judge, about an hour after I picked the doctor up in Willow Springs, Missouri.

"I wish to state at this time that there was no one taken into my confidence in this matter; that there was no one with me when I kidnaped the doctor and killed him near the pond on Highway No. 63, where his body was found; and that, furthermore, I did not take any money from this person after I had shot him, nor did I take his watch. I also wish to state that, there was no such person as the Nighthawk connected in this case with me and that I just thought of that name when I was questioned in Willow Springs, Missouri, by the officers and believed that that would be the best story to tell.

At the time I kidnaped the doctor I had no intention of killing him and my only reason for killing him was that I believed he was going to attack me when he made a jump for me and when he did that I emptied my gun in him."

Robert Kenyon/1937

Mourners Struggling to Find their Future

(Courtesy: Willow Springs News)

Over 1,000 flowers spray their grace over the casket of Dr. Davis. The funeral was attended by over 1800 people, both far and wide, with several speakers at the funeral, which was held in the Willow Springs High School gymnasium.

On a bitter cold day of Feb. 5, 1937, Dr. J.C.B. Davis was finally reunited with his beloved community and laid to rest. According to town historian, Ms. Ella Horak, Davis' funeral was the saddest and largest funeral ever held in Willow Springs. In a valiant effort to help her grieving hometown, Mrs. Davis insisted on her husband's casket first being present out in the front room of his medical clinic—his “second home”—where patients brought flowers, letters, and recollections of his kindness.

The funeral itself was held at the Willow Springs High School gymnasium, a place where Davis always enjoyed visiting with his students and as an educator of the school. Clergy from area churches delivered heartfelt eulogies, recalling Davis’ calm bedside manner, unwavering devotion, and willingness to drive miles on treacherous roads for the sick. One account described how “not a dry eye remained in the pews,” as the congregation filled songs of grief with tribute. Mourners included well-dressed city folk, rugged farmers, children, and even those he treated as charity cases—each drawn, bound by gratitude.

Regional newspapers noted that ambulances, accompanied by mourners on foot, formed a somber procession to the local cemetery, where the funeral service was reportedly overflowing. Local reports emphasize that Davis' funeral was a public event, with virtually the entire town turning out, as well as strangers far and wide, multiple law enforcement departments, including Sgt. Massie, who was instrumental and selfless in cracking the case, all to honor a man they considered a special member of Southern Missouri.

Davis' funeral served as a culmination of Willow Springs' grief and a hesitant yet necessary start to the healing process. The funeral of Davis also allowed patrons to return the favor and nurture the legacy of a beloved community caregiver. For its rural setting and admist a difficult Great Depression era, the scale and positve-emotion was extraordinary. Such an event also underscored how murderer Robert Kenyon would not get the "final word" to this senseless tragedy. His selfish intentions shattered not just one family but an entire region—transforming a personal tragedy into a communal heartbreak that resonated throughout Southern Missouri and even Nationwide. But in the end, mourners bonded together and rallied behind the legacy of Dr. J.C.B. Davis and somehow, all seemed to feel a little better, and that is what Dr. Davis would have wanted.

Kenyon vs. State of Missouri Trial Process & Conviction (July 1937- 1939)

Now that Dr. J.C.B. Davis was laid to rest, it was time for justice to be served. Robert Kenyon's trial took place in July of 1937 in Oregon County, after a change of venue from Howell County, due to pretrial publicity concerns. Kenyon was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death by gas chamber. However, Kenyon’s conviction was appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, which upheld the verdict.

Two years later, on April 28, 1939, after a long and anguishing court process for a still grieving Davis family and hometown community, Kenyon was executed in Missouri’s State Penintentiary. He was 24 years old.

A Series of Sad Firsts

The kidnapping and murder of Dr. J. C. B. Davis in January of 1937 resonated far beyond the city limits of Willow Springs, Mo., and easily captured the attention of newspapers "coast to coast". It was one of the rare small-town crimes that reached national headlines during an era when local tragedies seldom made the front page. The tragedy and trial of Dr. Davis' kidnapping and murder appeared in newspapers such as the St. Louis Globe‑Democrat, while wire services routed the story spanning from New York, Chicago, Boston and westward to Colorado and beyond—each emphasizing the shocking twist that the victim was made to write his own ransom notes. The fantastic efforts of law enforcement to bond together and find the killer, and the dramatic confession by 21‑year‑old Robert Kenyon, who claimed he needed the ransom money to buy his girlfriend some new clothes so they could get married, and the swift efforts of law enforcement in finding Dr. Davis’ body, and yes, the intense public fascination oh how "big city" crime could spread to the hay fields of small towns.

What truly intensified the national buzz was Missouri’s use of the newly established gas chamber rather than the traditional gallows. Robert Kenyon became the first person executed by lethal gas in Missouri on April 28, 1939, at the Jefferson City State Penintentiary— marking a sober milestone in criminal justice. Missouri had abandoned hanging just a year earlier, signaling a broader shift in execution methods nationwide. This pivot underscored public unease with older, visibly violent forms of capital punishment, and cemented the Davis case as not just a brutal murder, but a turning point—societally and legislatively—in how America dealt with its most heinous crimes.

(Courtesy: The Rocky Mountain News/Colorado, 1937)

Pictured above is the wife of Dr. Davis, Clara, who not only had to go through the tragedy of losing her husband but also endure the firestorm of newspaper coverage. Newspapers far and wide ripped headlines with fury from the facts surrounding the murder of Dr Davis. Some even coined Robert Kenyon as the "Stupid Slayer", because of his numerous blunders throughout the process of kidnapping and murdering a beloved caregiver of the community.

(Courtesy: National Newspaper Archives)

Law enforcement banding together and making history Nationwide! Multiple agencies included local police, sheriff departments and FBI. Pictured is Missouri State Highway Patrol Sgt. N.H. Massie, Willow Springs, Mo. He broke the early lead on the case and had only 18 hours of sleep in a week. Massie was the driving force behind bringing justice to the family of Dr. Davis!

As well, the swift and coordinated response by law enforcement in the Dr. J.C.B. Davis case was remarkably fast and effective for the 1930s', and it stood out as unusual for its time—especially in a rural area like Southern Missouri. After Dr. Davis disappeared on January 26, 1937, local authorities in Howell County quickly realized this was more than a missing person case. The Missouri Highway Patrol Troop G, still a relatively young agency (founded in 1931), played a key role by coordinating roadblocks and conducting early searches.

The FBI, newly empowered by the 1934 Federal Kidnapping Act (often called the "Lindbergh Law"), became involved within days due to the ransom element. This allowed federal jurisdiction over what was previously considered a state matter. Investigators from multiple agencies—including state troopers, local sheriffs, and federal agents—acted swiftly, following handwriting leads, physical clues (like the doctor’s medical kit).

And last but certainly not least, for the hometown eyewitnesses who were not afraid to get involved and thus, provided vital information that truly expedited to break the case and capture the murderer, Robert Kenyon. These "everyday heroes" didn't hesitate to come forward and help a region get the answers that they so desperately needed, and this in itself was enough to inspire appreciation from those far and wide.

Gone Too Soon

Today, Dr. J.C.B. Davis rests in Willow Springs Cemetery beside his beloved second wife Clara and not far from the roads he once traveled to deliver babies, tend to the sick, and comfort the dying. His grave is simple, but for those who remember, it’s a powerful symbol of a life lived in service—and a death that jolted a community.

Because even in our small towns, where life moves slower and the world feels a little safer, there are moments that shake the ground beneath our feet. Tragedy, when it strikes, feels more personal, more intimate. But just as the trees regrow after winter, so too does the spirit of a town rebuild itself through resilience, remembrance, and grace. This is Willow Springs, Mo. testimony.

And while those who knew Dr. Davis: devoted family, ailing patients, diligent investigators and grief stricken community neighbors are long gone, his story remains etched in the memory of Willow Springs—not just as a warning of what was lost, but as a reminder of what must be preserved: compassion, vigilance, and the unshakable bonds of a close-knit community. Dr. Davis' spirit of optimism is the kind of stuff that is good for healing the soul and he would of liked that.

Resting peacefully, Dr. J.C.B. Davis and his second wife, Clara, in the Willow Springs City Cemetery. Their son, Harold Davis, is also buried in the same cemetery. Cleora, daughter of Dr. Davis and his first wife, Mildred, is buried in another state.